Professor Alice Sullivan, Director of the 1970 British Cohort Study, gave her professorial lecture at the UCL Institute of Education earlier this summer, summarising the highlights of her academic career so far. In this blog she outlines her presentation.

Much of my work concerns the way that advantage and disadvantage are passed down from one generation to the next. So, for example, why do middle class kids do better in education than working class kids? And, why is there a link between social class origins in childhood and socioeconomic destinations in adulthood?

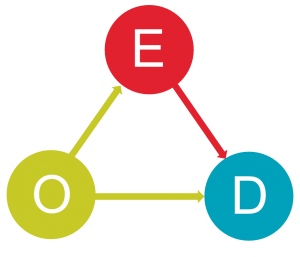

Sociologists sometimes call this relationship the OED triangle, where O stands for socioeconomic origins, E stands for Education and D stands for destinations in adult life. Social reproduction occurs when there is a close relationship between origins and destinations, and social mobility when that relationship is broken by a move up or down the social ladder.

Sociologists sometimes call this relationship the OED triangle, where O stands for socioeconomic origins, E stands for Education and D stands for destinations in adult life. Social reproduction occurs when there is a close relationship between origins and destinations, and social mobility when that relationship is broken by a move up or down the social ladder.

During the course of my career I’ve worked on a set of interrelated questions regarding educational and social inequalities, and these are the questions I will address here.

- Why are there social class gaps in education, and what is the role of cultural capital in explaining those gaps?

- What is the influence of school? How much does it matter whether you attend a single-sex, grammar or private school?

- What is the role of reading for pleasure in learning during both youth and adult life?

- How do parents pass language skills down to their children?

Cultural capital and educational attainment

Pierre Bourdieu describes cultural capital as “…linguistic and cultural competence and that relationship of familiarity with culture which can only be produced by family upbringing when it transmits the dominant culture.” (Bourdieu 1977).

As a student, this idea had plausibility to me, but seemed rather nebulous (Sullivan 2000; Sullivan 2002). I wanted to pin it down. I distinguished three elements to the concept of cultural capital: participation, language and familiarity or knowledge (Sullivan 2007). Not many studies had tried to measure cultural capital, to operationalize and quantify it, and those that had had typically looked at high culture, such as going to art galleries and museums. I suspected that this might miss something important. I was interested in how culture is absorbed and becomes language and knowledge.

As part of my PhD I designed a questionnaire to look at young people’s activities, language skills and cultural knowledge, and went into schools to survey 465 15-16 year olds (Sullivan 2001).

One of the distinctive feature of the questionnaire was a test of cultural knowledge that I developed. This was a multiple choice test, and respondents had to decide whether cultural figures were associated with art, music, science, politics or literature.

Some cultural figures were of course more well known to the teenage respondents than others, and it’s surprising how little known some supposedly famous figures were. In politics, Bill Clinton, at over 90 per cent, was rather more well-known than Karl Marx, at 25 per cent. And in literature, the vast majority (89%) knew who Charles Dickens was, but just five per cent had heard of Martin Amis. What we think of as shared cultural knowledge is often far from universal.

Importantly, I found that taking part in certain cultural activities, like reading, tended to have a bigger impact on GCSE results than others, like going to art galleries and museums for example. And both cultural knowledge and language scores helped to explain the link between cultural activities and academic results.

With colleagues, I developed this work for the Oxford University admissions study (Zimdars, Sullivan and Heath 2009), and found that cultural knowledge also helped to explain which applicants to Oxford University were admitted and which weren’t.

The British cohort studies

Britain has an amazing tradition of national birth cohort studies, which started in 1946 (Pearson 2016). CLS manages three birth cohorts, born in 1958, 1970 and 2000, and a youth cohort (Next Steps) which fills the gap between the 1970 and 2000 cohorts.

During my time at CLS, I’ve worked on all of these inspiring studies. And in 2010 I had the privilege to become director of the 1970 cohort. What’s extraordinary about these studies is that they follow people from cradle to grave, tracking an incredible level of rich detail about their lives.

Single-sex and co-educational schooling

One of the first projects I worked on using birth cohort data was with Heather Joshi and the sadly now late Diana Leonard, using the 1958 cohort to compare boys and girls who had been to single-sex and co-educational schools. If we go back to the 60s and 70s when the 58 cohort were at school, there was a view that co-educational schools were inherently progressive, and single-sex institutions outdated. Co-educational schools were more ‘natural’, as RR Dale explained in his influential text ‘Mixed or Single-sex School’.

“That men and women are complementary is a biological fact. That they also influence each other’s conduct – from the gift of flowers to the hurling of the kitchen utensils – is an inevitable accompaniment of life in a bisexual world. A family has a father and a mother; lacking one of these each feels incomplete and unsatisfied…So it is with other institutions when they are one-sex – as we know from the homosexual activities in Public School…” (Dale 1969).

This view had been challenged by some feminists who thought that girls missed out in mixed schools. However, this has long been a topic where strong opinions have flourished in the absence of rigorous evidence. The 1958 cohort provided the perfect opportunity to test empirically whether girls and boys of this generation fared differently in single-sex and mixed schools, while controlling for previous test scores, socioeconomic status, etc. We found that in fact girls had done better academically in single-sex than co-ed schools, whereas for boys it seemed to make no difference to overall attainment. One of the most striking findings was about subject passes, where single-sex schools did seem to affect boys as well as girls. Girls at single-sex schools were more likely to gain science A-levels compared to those in co-ed schools, whereas boys in single-sex schools were more likely to gain language passes (Sullivan, Joshi and Leonard 2010). And going to a single-sex or co-educational school was even linked to how able girls and boys thought they were in different subjects (Sullivan 2009). The surprising upshot was that mixed sex schools appeared to enforce traditional gendered norms more strongly than single-sex schools.

Elite education and social reproduction

Of course, when we think of the role of schooling in social mobility and social reproduction in Britain, it’s the role of private and grammar schools that looms large. Our ruling elite continues to be dominated by individuals with a certain educational background. I’ve carried out work on this question of elite education and destinations with colleagues using both the 1958 and 1970 birth cohorts. We were interested in uncovering the role of private and grammar schools, but also of education, and especially elite education, more generally.

We investigated the link between secondary school type and the educational routes people took later on. In the 1970 cohort, people who went to private schools were not just the most likely to get a degree, but were also far more likely than pupils from other types of school to get a degree from one of the most selective ‘elite’ universities (Sullivan et al. 2014).

Looking at the pathways from social origins in childhood to occupational destinations at age 42, education was the most important driver at an individual level. However, while education broadly explained the socioeconomic gap in outcomes, the same is not true for the sex gap. Women born in 1970 were far less likely than men to have jobs classified as being in the top social class by the time they were 42 compared with men, and this couldn’t be explained by their educational attainment (Sullivan et al. 2018).

We also looked at how things changed between the 1958 and 1970 born cohorts. This work (not yet published) showed some interesting changes in the pathways between childhood origins and adult social class and income. For the more recent cohort, inequalities in childhood cognitive attainment (assessed via a battery of tests taken by the cohort members during childhood) declined, but childhood cognition became a less important predictor of academic attainment. Private schools became less socially selective, and more academically selective, and more strongly linked to positive educational outcomes for their pupils. These changes may well be attributed to the decline of grammar schools. Nevertheless, while the pathways to educational and occupational attainment changed between the 1958 and 1970 cohorts, we found no overall change in the strength of the link between their childhood origins and adult destinations.

Reading for pleasure

Education is about more than just social mobility, it is fundamentally about learning, and learning isn’t something that only happens within schools. One of the great things about longitudinal data is that you can look at change over time, which is a boon if you are interested in learning. My colleague Matt Brown and I looked at how much time children spent reading for pleasure, and examined whether that influenced progress in vocabulary and maths up to age 16 using the 1970 cohort study (Sullivan and Brown 2015a). We all know that bright children who are doing well at school are more likely to read for pleasure, but with longitudinal data we are able to compare like with like, and ask whether children who read actually progress more in their learning over time compared to similar children who don’t read for pleasure. We then followed up to see whether reading in adulthood made a difference to vocabulary at age 42 (Sullivan and Brown 2015b).

Our findings were dramatic. Controlling for children’s socioeconomic backgrounds and test scores up to age ten, those who read for pleasure made more progress, not just in vocabulary, but also in maths. Most strikingly, the difference made by reading was four times greater than the difference made by a parent’s education, which is typically the variable that sociologists of education would expect to be most powerful in our models.

But what happens to language development once our school years are behind us? At age 42, we asked the BCS70 participants about their reading habits, and also repeated the same vocabulary test that they had taken at age 16. This gave us the opportunity to assess how much their word power had increased between the ages of 16 and 42.

One piece of good news is that learning doesn’t stop at the end of the school years. In fact, our study members demonstrated large gains in vocabulary between the ages of 16 and 42. At age 16, the average vocabulary test score was 55 per cent. By age 42, study members scored an average of 63 per cent on the same test.

Another piece of good news is that reports of the death of reading seem to have been greatly exaggerated. Over a quarter (26%) of respondents said that they read books in their spare time on a daily basis, with a further 33 per cent saying that they read for pleasure at least once a month. This leaves a minority of 41 per cent who said that they read in their leisure time only every few months or less often. However, women read far more often than men. 40 per cent of men said that they read in their spare time once a year or less compared to 18 per cent of women.

So, who improved their word power the most between the ages of 16 and 42? Our statistical analysis took account of differences in people’s socioeconomic backgrounds and in their vocabulary test scores at the ages of five, ten and 16. We found that reading for pleasure in both childhood and adulthood made a difference to rates of vocabulary growth between adolescence and mid-life. Childhood reading for pleasure exerted a long-term positive influence on vocabulary development up to age 42. In addition, those who read for pleasure frequently at age 42 experienced larger vocabulary gains between adolescence and mid-life than those who did not read.

And it seems that it isn’t just how much you read, but also what you read that makes a difference. People who read ‘high-brow’ fiction (such as classic fiction and contemporary literary fiction) made the greatest vocabulary gains.

The intergenerational transmission of vocabulary

I have continued my work on language using the most recent British cohort, born at the turn of the millennium (Sullivan, Moulton and Fitzsimons 2017). We were able to use the same vocabulary test that the 1970 cohort had taken at 16 and at 42, and administer this to both the millennium cohort at age 14 and to their parents. That gave us the unique resource of a large cohort study with language scores for both parents and offspring.

This is exciting because previously we only had small scale studies looking at the transmission of language from parents to children. Perhaps the most influential prior study on this question was based on only 42 families in one US university town (Hart and Rinsley 1995). Whereas our study used data from around 12,000 families.

What we found was that there were large differences in parents’ vocabularies according to parental education and ethnic group. And vocabulary was powerfully transmitted from parents to children. However, there is cause for optimism, in that the socioeconomic and ethnic gaps among children were far smaller than for their parents.

We also found again that, taking all other things into account, reading for pleasure was still a powerful driver of vocabulary for this generation.

Conclusion

Education is the most powerful predictor of individual socioeconomic outcomes, yet changing the education system is no guarantee of changing the level of social mobility in society. And perhaps those of us who care about education should focus less about this, for two reasons.

As the sociologist Christopher Jencks remarked, the point is to reduce inequality, not to randomise it (Jencks 1972).

And education is not just a positional good, something you have to do to get a job. A purely instrumental approach to education ignores the power of books and learning, and the liberatory gift of independent learning, critical thought and imagination.

References:

Bourdieu, P. 1977. “Cultural Reproduction and Social Reproduction.” in Power and Ideology in Education, edited by J. Karabel and A.H. Halsey. Oxford: OUP.

Dale, R.R. 1969. Mixed or Single-sex School? Volume I. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul.

Hart, B., and T.R. Rinsley. 1995. Meaningful differences in the everyday experiences of young American children. Baltimore, M.D.: Paul H. Brookes.

Jencks, C. 1972. Inequality: A Reassessment of the Effect of Family and Schooling in America. New York: Basic Books.

Pearson, Helen. 2016. The Life Project: The extraordinary story of our ordinary lives: Penguin UK.

Sullivan, A. 2000. “Cultural Capital, Rational Choice and Educational Inequalities.” D.Phil. Thesis, University of Oxford.

Sullivan, A, and M Brown. 2015a. “Reading for pleasure and progress in vocabulary and mathematics.” British Educational Research Journal 41(6):971-91.

—. 2015b. “Vocabulary from adolescence to middle age.” Longitudinal and Life Course Studies 6(2):173-89.

Sullivan, A, V Moulton, and E Fitzsimons. 2017. “The intergenerational transmission of vocabulary.” University College London CLS Working Paper 2017/14.

Sullivan, A, S Parsons, F Green, R.D. Wiggins, and G Ploubidis. 2018. “The path from social origins to top jobs: social reproduction via education.” The British journal of sociology 69(3):776-98.

Sullivan, A, S Parsons, R Wiggins, A Heath, and F Green. 2014. “Social origins, school type and higher education destinations.” Oxford Review of Education 40(6):739-63.

Sullivan, A. 2001. “Cultural Capital and Educational Attainment.” Sociology 35(4):893-912.

—. 2002. “Bourdieu and Education: How Useful is Bourdieu’s Theory for Researchers?” Netherlands’ Journal of Social Sciences 38(2):144-66.

—. 2007. “Cultural Capital, Cultural Knowledge, and Ability.” Sociological Research Online 12(6).

—. 2009. “Academic self-concept, gender, and single-sex schooling.” British Educational Research Journal 35(2):259-88.

Sullivan, A., H. Joshi, and D. Leonard. 2010. “Single-sex Schooling and Academic Attainment at School and through the Lifecourse.” American Educational Research Journal 47(1):6-36.

Zimdars, A., A. Sullivan, and A.F. Heath. 2009. “Elite higher education admissions in the arts and sciences: Is cultural capital the key?” Sociology 43(4):648-66.

This article was first published on the IOE London Blog.