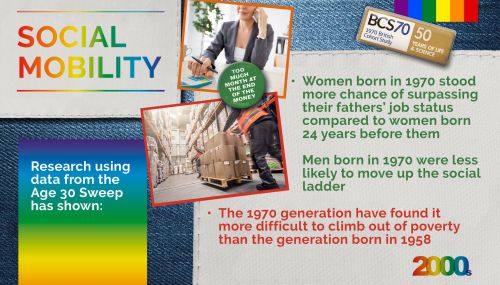

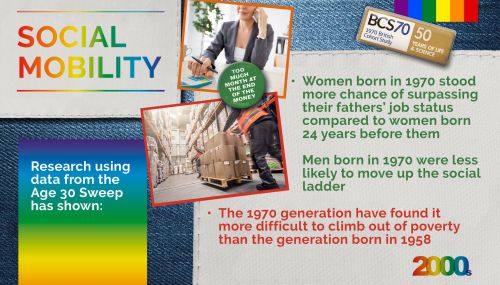

Important discoveries from the 1970 British Cohort Study – Social mobility

50 stories

19 November 2020

“The social mobility debate in the last few years was ignited by those comparisons of the 1958 birth cohort and the 1970 birth cohort. And it looked as if there was less mobility for the 1970 cohort study than the 1958. So that’s a very powerful finding.”

Lord David Willetts, former coalition government Minister for Science and Universities, and Conservative MP speaks about the importance of the 1970 British Cohort Study in informing debates on social mobility in our 50 Years of Life in Britain podcast series. Listen here.

Creating a fairer society, where people are able to flourish and fulfil their potential, no matter where they started out in life, has been an enduring policy focus for successive governments.

Social mobility assesses how much people’s early life circumstances are linked to their outcomes in adulthood, showing how fair, fluid and meritocratic a society actually is.

The 1970 British Cohort Study (BCS70) has been one of the leading sources of evidence on social mobility, informing a series of impassioned academic debates on this topic.

In research on social mobility, BCS70 is often used in conjunction with similar studies of people born in 1946 and 1958 to understand whether equality of opportunity, and social mobility has either increased or decreased between generations.

When BCS70 members were children their parents were asked about their income, what they did for a living, and their education. Then, as study members themselves grew up, they gave information about their own educational qualifications, employment and income.

Many politicians across the political spectrum believe that social mobility declined for members of BCS70 compared to the 1946 and 1958 study members before them. However, sociologists and economists studying the issue can’t quite agree whether this is actually the case.

While sociologists look at the proportion of individuals who are found in a different occupational social class to that of their parents, economists look at the rates of people who progress to a different income bracket.

According to research by one group of sociologists, more than three quarters of men taking part in BCS70 ended up in a different social class to that of their fathers by age 38 – roughly the same proportion as those taking part in the 1946 and 1958 studies. However, for BCS70 women, rates of social mobility increased slightly compared to those taking part in the earlier studies.

Men born in 1946 were two to three times more likely to move up in social status rather than down. However, by age 38, BCS70 men were only about a third more likely to move up than down. Women were equally as likely to move in either direction by this age.

Economists, using income to measure mobility, found that the BCS70 generation had experienced less mobility than those born 12 years before them. For example, of the men born in 1970 who grew up in the poorest families, 38% were themselves among the lowest earners at age 34. Only 11% made it from the bottom to the top income bracket. By comparison, those born in 1958 had greater odds of moving up the income ladder; 30% of men who had been in the bottom income bracket at age 16 were there at age 33, but 18% had risen to be among the top earners.

In 2011, the coalition government drew on these findings in its social mobility strategy, Opening Doors, Breaking Barriers. By continuing to follow BCS70 members’ lives, and those of younger generations in Britain, we can learn more about the inequalities in our society and how to tackle them.

Read more: Recent Changes in Intergenerational Mobility in Britain (2007)

The mobility problem in Britain: new findings from the analysis of birth cohort data (2015)

Back to news listing